Patch Trading

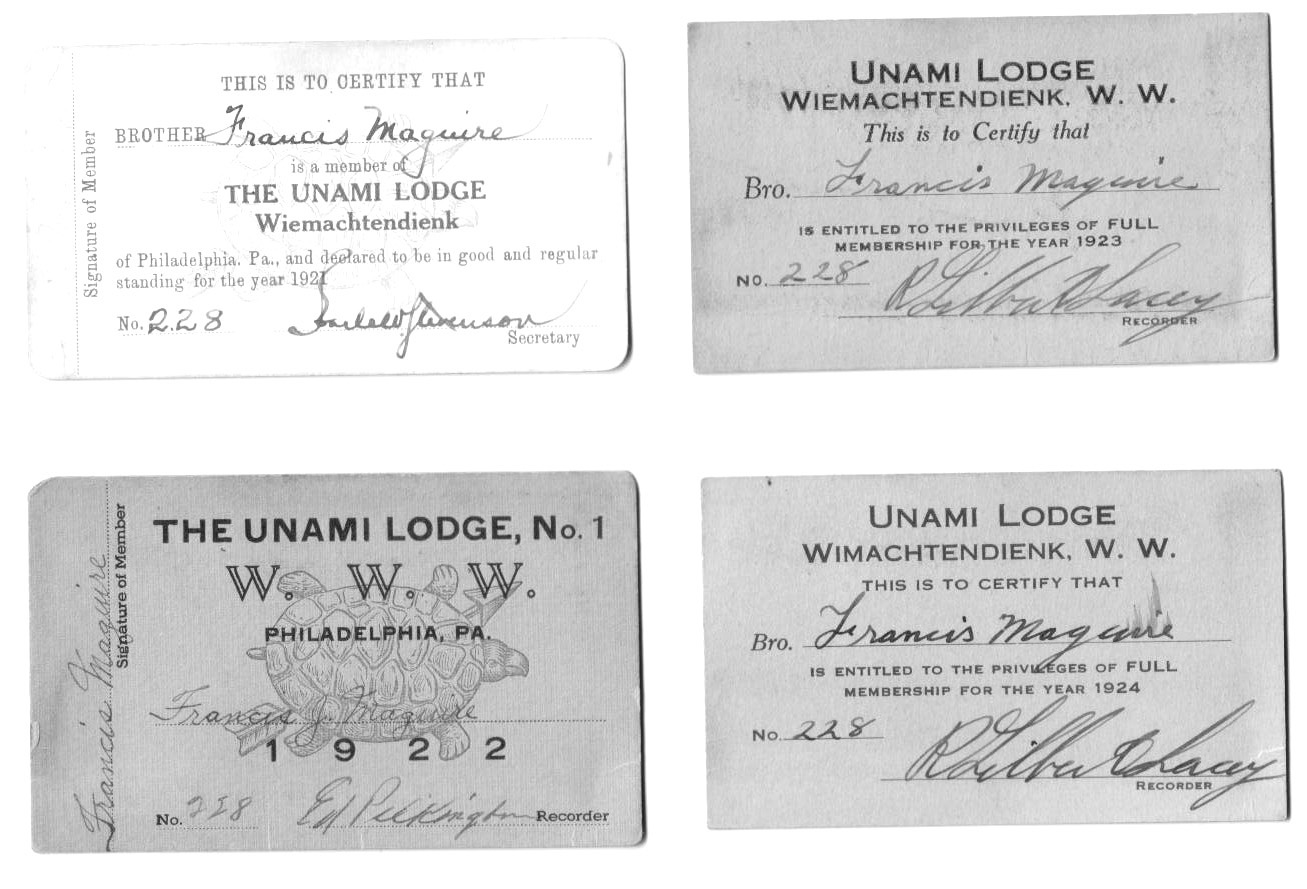

Nobody knows when the first swap of Order of the Arrow emblems took place, but it had to be soon after the first badges of Wimachtendienk appeared. In the early years there was no trading of OA insignia. The first insignia in 1916 were pins. Pins were made of silver or gold. They were relatively expensive, certainly when compared to patches. An Unami Lodge gold Second Degree pin in 1919 might have cost $2.00; the cost of 20 die-cut felt camp monogram patches. No one was trading them with each other.

At the first Grand Lodge Meeting in 1921 most of the delegates were professional Scouters. They had much to discuss, but they were not trading. The first badges of the Order were issued shortly thereafter. The first chenille shaped badge from Minsi Lodge of Reading, Pennsylvania was issued circa 1922. But there was really no one to trade it with and no real location to wear it (OA Insignia was forbidden from the uniform until 1942, and that was for just the Universal Arrow Ribbon.) It was not until 1945 that pocket patches (not flaps) were approved for uniforms.

Circa 1925 Ranachqua Lodge from the Bronx, New York issued a chenille. At the following Grand Lodge Meeting in 1926 a motion was made to fully authorize OA patches. The motion was approved, however a requirement was made that only Brotherhood / Second Degree members or above could have them. With such stringent patch restrictions there still was virtually no trading of Wimachtendienk emblems going on.

The earliest example of a multiple OA emblem collection came from an Arrowman in Minsi Lodge. He had only three patches, but they were from different lodges. That meant he either swapped them or was given them as he was only in one of the lodges. The first badge in the collection and only one previously known to collectors was a Minsi Lodge chenille dating to circa 1927. The other badges, dated to the same period, were from Unami Lodge and from Swatara Lodge, Lebanon, Pennsylvania.

By the 1930s swapping had begun at meetings of the Grand Lodge. In 1933 at the Chicago hosted Grand Lodge Meeting there would have been patches everywhere to be seen; not so many OA emblems, but camp patches and World’s Fair patches. Chicago was already using a system of year badges and activity badges on their neckerchiefs. Swapping would have taken place, although probably not much involving OA emblems. The trades were done in fellowship. It was an exchange to remember a brother from another lodge. By 1936 at the Grand Lodge Meeting that had changed. Arrowmen were trading patches. There is a reference in the 1938 National Meeting Minutes that states, “once again badge swapping was a popular activity at the meeting”. The earliest photograph of OA badge trading was taken at the 1938 meeting held at Camp Irondale, Missouri.

On February 19,1937 the National Executive Committee in a letter to Scout Executives asked them in their role as Supreme Chief of the Fire,

to stress to his Order of the Arrow members attending the (1937) Jamboree, that they should not swap or exchange Order of the Arrow insignia.

It is not known why such an admonishment was made and there was never a written order rescinding of the policy. It is known that OA patch trading took place at the 1937 National Jamboree with multiple collections documented from the event.

By 1940, patch “swapping” was a major pastime for Arrowmen at national, regional and area events. In general it was “one for one” trading. It did not interrupt program and was done in fellowship. Many Arrowmen when they left the Order and moved on from patch swapping would give the patches to younger lodge members to trade and have fun with.

Up until 1948, there were no books or guides that had pictures of OA patches. J. Rucker Newbery collected OA patches, or as he would have called them, emblems. He called them emblems because they were “emblematic” meaning they stood for something (a fact often lost when patches are made for no reason other than for them to be rare or collected). In 1948 Newbery edited the first Order of the Arrow Handbook. In the book he included two pages devoted to pictures of emblems. This gave some lodges the impetus needed to create their own emblem for the first time. The badges were also really wonderful looking and, to many of the thousands of Arrowmen that bought the handbook, were fascinating. The patch-trading hobby was spreading rapidly.

In 1952 Dwight W. Bischel published his Wabaningo Lodge Emblem Handbook (The “Wab” book). Inside the Wab book Bischel provided all sorts of information never offered to Arrowmen. Each lodge that was known to have an emblem was listed in lodge number order and the badge was photographed if available. Other pertinent information such as city and state of the lodge, council name, meaning of name, etc. was listed. The colors of the patches were also listed because the Wab book was not printed in color. The book was actively promoted in the OA National Bulletinand at the National OA Conference. Bischel quickly sold-out 2,000 copies of the book in under a year. A generation of patch collecting Arrowmen emerged.

The patch-trading hobby continued to grow throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Hobby newsletters were developed such as The Trader which emerged following the 1953 National Jamboree and was first edited by Mike Diamond. It was during the 1950s that the OA started to make flaps in large quantities. Once Arrowmen could collect the same shaped patch from every lodge neatly cataloged in number order the hobby accelerated amongst Arrowmen.

The patch-trading hobby continued to grow throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Hobby newsletters were developed such as The Trader which emerged following the 1953 National Jamboree and was first edited by Mike Diamond. It was during the 1950s that the OA started to make flaps in large quantities. Once Arrowmen could collect the same shaped patch from every lodge neatly cataloged in number order the hobby accelerated amongst Arrowmen.

Just as with any thing that is new and explodes in interest, problems developed. When Arrowmen learned that Bischel had obtained the badges by writing to council offices many traders started writing to council’s seeking patches. Some offices liked making the extra money or had a relationship with an Arrowman more than glad to have a new patch trading pen pal. Other found it to be a major distraction having to devote personnel to return unwanted money or patches sent by a hopeful Scout. In 1960 the OA made an official statement that Arrowmen were not to write to council offices for patches.

Other problems involved “restrictions” on patches. This made patches unequal in trade and caused a loss of fellowship. National strongly recommended an end to restrictions in late 1975. The biggest problem though was from a minority of over-zealous traders who were disrupting actual program because they were only present to trade patches. To be sure, the great majority of patch traders were active Arrowmen giving service and trading some patches along the way. In 1977 the NOAC theme show actually vilified a flap trader for not having the correct spirit. They showed him with a brief case full of patches, skipping training and having no idea of the purpose of the OA. Within the patch trading community the hobby changed.

One part of the change was that patch “traders” were becoming patch “collectors”. There was a heightened awareness that program must come first and that collectors needed to police themselves. More books were being produced. National and regional books were being written and published that provide the history of insignia. Arrowmen started paying more and more attention to their locally issued items. Patch organizations such as National Scout Collectors Society, Western Traders Association, the American Scouting Historical Society and American Scouting Traders Association (ASTA) and later the International Scout Collectors Association (ISCA) formed. They included a code of ethics. Among rules were not mailing council offices and not trading during training sessions and always following the rules of the event (whether they agreed with them or not).

One part of the change was that patch “traders” were becoming patch “collectors”. There was a heightened awareness that program must come first and that collectors needed to police themselves. More books were being produced. National and regional books were being written and published that provide the history of insignia. Arrowmen started paying more and more attention to their locally issued items. Patch organizations such as National Scout Collectors Society, Western Traders Association, the American Scouting Historical Society and American Scouting Traders Association (ASTA) and later the International Scout Collectors Association (ISCA) formed. They included a code of ethics. Among rules were not mailing council offices and not trading during training sessions and always following the rules of the event (whether they agreed with them or not).

Starting in the 1960s and gaining in popularity through 2000 were events separate from program only for traders. They were called “Trade-o-rees”. By the 1970s a National Trade-o-ree was held in conjunction with each National OA Conference or Jamboree. Many lodges learned to host trade-o-rees as fundraisers often including a memorabilia auction. The first “official” trade-o-ree at a NOAC was at the 2009 Conference held on campus at the University of Indiana.

The patch trading groups that had developed were also publishing magazines that provided information for collectors. This had the affect of converting what were patch “collectors” in the 1980s and 1990s to Scout “historians” in the 2000s. More and more collectors were interested in preserving the insignia of their lodge, camp or council through the insignia that had been issued. Because the insignia became collectible, value became associated with the memorabilia. During the past 15 years unbelievable values have been associated with rare OA insignia. This is a measure of the passion of Arrowmen for their history.

Collectibles of all types have passion and value associated with them. But OA insignia is different than something like a baseball card. A baseball card never plays the game of baseball. In most cases the card is never even touched by the player depicted or anyone else in Major League Baseball. But OA insignia had to be earned by an Arrowman. The emblem represents the presence and service of an elder brother.

A fortunate by-product of the passion and swapping and trading over the years is the Order of the Arrow’s insignia has been preserved for posterity. Books such as The Blue Book - Standard Order of the Arrow Insignia Catalog, edited by Bill Topkis and websites like the Internet Guide to OA Insignia published by John Pannell along with exhibitions such as the OA Center for History at NOAC or the 2010 Mysterium Compass Vault at the 2010 National Scout Jamboree have made it possible for Arrowmen to continue to meet their obligation by observing and preserving the traditions of the Order of the Arrow.

The patch-trading hobby remains strong. Walk through any Jamboree or NOAC (when program is not going on, please) and patch trading can be found in almost every nook and cranny.

Awards, Background, Insignia, National Event, OA, Profile, Scouting